CHAPTER XVI

THE CENTRAL AND SOUTHERN PHILIPPINES

Concurrently with Fourteenth Area Army's protracted delaying action in the key mountain redoubts of Luzon, Thirty-fifth Army, fully aware that there was no hope of obtaining further reinforcement, sought as best it could to carry out a similar policy of prolonged resistance in the central and southern Philippines.1

On 20 December General Yamashita dispatched an order to Thirty-fifth Army directing abandonment of the decisive battle on Leyte.2 The substance of this order, delayed two days in transmission, was as follows:3

1. The Thirty-fifth Army will hereafter continue unbroken resistance in its assigned operational area and will support future counterattacks by Japanese forces.

2. The Army, in particular, will endeavor to secure the air bases at Bacolod, Cagayan and Davao and prevent their seizure and use by the enemy.

Shortly thereafter, Lt. Gen. Suzuki, Thirty-fifth Army Commander, ordered the 30th Division commander, who was still awaiting transportation to Leyte,4 to remain on Mindanao and assume responsibility for defending that portion of the island east of Lanao Province.5 Subsequently, Army headquarters transmitted to all subordinate units, other than those on Leyte, the same order which had been received from Fourteenth Area Army on 22 December.6 (Plate No. 128). The interpretation and execution of this order was left entirely to the discretion of each individual commander in view of the belief prevailing in Army headquarters that it was unnecessary, at this time, to prepare detailed plans covering subsequent operations.7

In the first place, the Army Commander estimated that the enemy, rather than undertake the task of mopping up the Japanese forces in the remainder of the central and southern Philippines, would first employ all his forces in a massive assault against Luzon, and then continue his advance northward against the

[528]

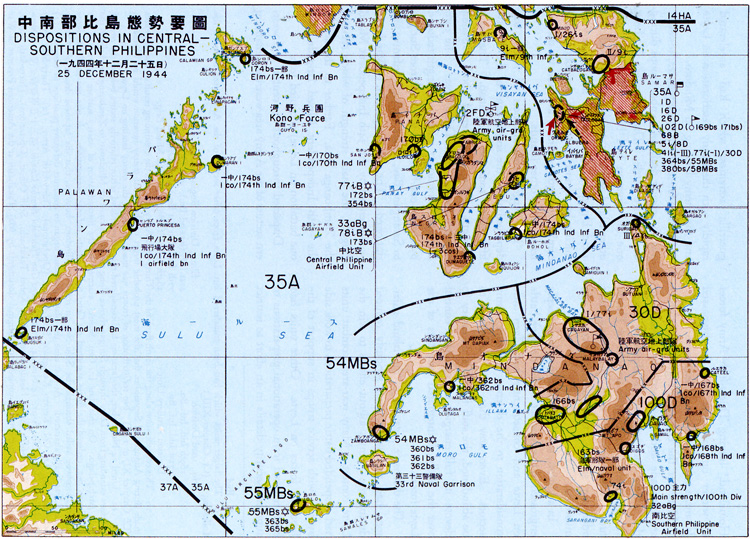

PLATE NO. 128

Dispositions in Central-Southern Philippines, 25 December 1944

[529]

Homeland,8 leaving Thirty-fifth Army forces to wither on the vine like the by-passed Japanese troops in the southeast area.

Moreover, the enemy's progressively tighter sea blockade and air superiority throughout the central and southern Philippines clearly ruled out any long distance transfer of Thirty-fifth Army troops, even presuming that adequate surface transportation could be mustered.

In addition, the Army staff had been deeply engrossed in the conduct of the decisive battle on Leyte and consequently had given little consideration to the defense of other Army sectors. Even now that this battle was to be abandoned, the staff found it necessary to devote its full energies to regaining control over the badly disintegrated remnants of the Leyte forces.

The defensive potential of the island garrisons had meanwhile been seriously reduced during the Army's all-out efforts to win the Leyte contest. Many rear-area combat units had suspended battle preparations to work side by side with service troops in support of the Japanese forces on Leyte. Other units had been relieved from operational preparations to augment security details in an effort to restrict guerrilla activities, which had accelerated rapidly with the steady deterioration on Leyte and the enemy landing on Mindoro.

Of more far-reaching consequences, however, was the steady drain of combat troops during the decisive battle. The equivalent of about one full division had been withdrawn from other island garrisons, principally the 30th and 102d Divisions, and poured into Leyte,9 reducing by almost one-fourth the total Army combat strength originally available for the defence of the other islands.

The largest concentration of forces was deployed along the south flank of the Thirty-fifth Army zone, on Mindanao.10 The main strength of the unweakened 100th Division was still located in the Davao area. The 30th Division, its nuclear infantry strength reduced by almost one-half, was scattered from Surigao to Sarangani Bay, where the 74th Infantry was stationed. The western portion of Mindanao was defended by the 54th Independent Mixed Brigade, the main strength of which secured the Zamboanga area. Farther to the south, the 55th Independent Mixed Brigade (less one battalion on Leyte) occupied Jolo.

Dispersed throughout the central and western sectors of the Army area were the remaining

[530]

elements of the 102d Division.11 The strongest concentration was on Negros in the area around Bacolod. All Army ground forces on Palawan, Panay, Negros, and the small neighboring islands were under the command of Maj. Gen. Takeshi Kono, commander of the 77th Infantry Brigade, 102d Division.12

In addition to the Army ground forces, approximately 14,000 Navy ground combat troops and about 15,000 naval air and service personnel were stationed mainly at Cebu, Davao and Zamboanga.13 Both the 33d Special Base Force at Cebu and the 32d Special Base Force at Davao and Zamboanga were under the command of Southwest Area Fleet. The commander of the 33d Special Base Force, Rear Adm. Kaku Harada, exercised operational control over Army ground units stationed in the vicinity of Cebu by virtue of an earlier agreement with Lt. Gen. Suzuki.14

The 2d Air Division, under command of the Fourth Air Army, continued to carry out intermittent special-attack sorties with the few planes still operable. Air ground units of this division were widely dispersed over Palawan, Panay, Negros, Cebu, Mindanao and Jolo.15 The First Air Fleet had few planes in the area at this time, although base service elements of the Central Philippine Airfield Unit and of the Southern Philippine Airfield Unit were stationed at Cebu and on Mindanao, respectively.16

With the exception of the area near the city of Cebu, unified command over Army and Navy forces in each area would become operative only after an enemy landing, when the senior military commander would assume operational control over all forces present. Prior to such invasion, all forces merely co-operated in defensive preparations under the supervision of the senior commander.

Such was the over-all situation of the Japanese forces defending the central and southern Philippines on 25 December, when the enemy launched a new amphibious landing in the rear of the shattered Thirty-fifth Army remnants on northwestern Leyte. This assault, delivered in the Palompon area, virtually shattered all hope of prolonged resistance by Lt. Gen. Suzuki's forces.

The disintegration of the Japanese remnants on Leyte now began to accelerate rapidly. Upon learning of the new enemy landing near Palompon, Lt. Gen. Suzuki quickly charged the defense of that area to nearby service troops, the only forces then available.

On the following day, 26 December,17 Lt.

[531]

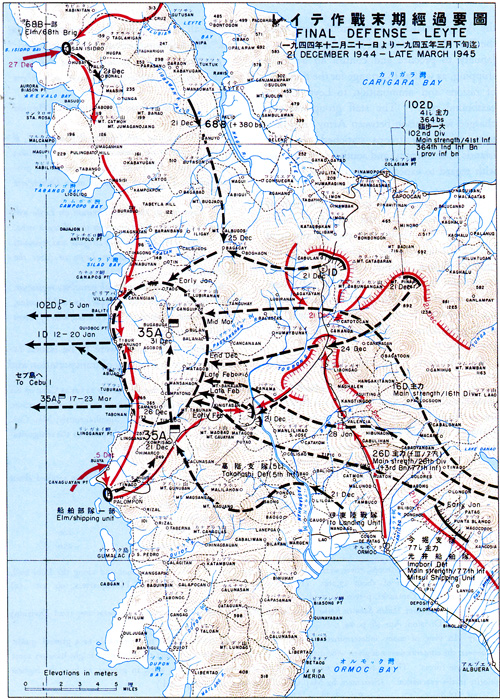

Gen. Suzuki revoked an earlier order for a general withdrawal into the Palompon area and drew up new plans to assemble the remnants of his forces farther north in the vicinity of Mt. Canguipot.18 (Plate No. 129) Orders to this effect could be issued, however, only to units in the vicinity of Army headquarters. Other forces were to be notified upon arrival in the general area. On the same day the Army command post began displacing from Kompisao to the southern slope of Mt. Canguipot.19

No sooner had this change been effected than the enemy launched still another amphibious move, constricting still further the Leyte forces. This new landing was made on 27 December at San Isidro and Calubian, neutralizing the harbor facilities in that area. Only weak service elements and the rear echelon of the 68th Brigade defended this sector.

The Army had meanwhile redoubled its efforts to re-establish contact with the forces isolated northeast of Ormoc and with the 16th and 26th Division survivors in the hills along the Lubi trail. The remnants of the 1st and 102d Divisions, which had been isolated in the Mt. Catabaran area east of Highway 2, were now arriving in the Canguipot area after infiltrating across the enemy-controlled highway.20

While the general withdrawal continued, Thirty-fifth Army received from Fourteenth Area Army on 28 December another order reiterating the necessity of prolonging resistance in the Army area but also directing the gradual evacuation of Leyte. The substance of this order was as follows:21

1. Thirty-fifth Army will henceforth adhere to a policy of self-sufficiency and independent combat designed to prolong resistance.

2. Troops on Leyte will be evacuated gradually to other islands.

3. It is suggested that Thirty-fifth Army headquarters move to a point suitable for over-all command of the Army.

With confusion now increasing daily as the enemy pressed his attacks from the north, east and south, the Army staff began preparing plans to implement this new Area Army order. From the outset considerable doubt was entertained as to the probable success of such a mass evacuation. The enemy's tight sea blockade precluded daytime movement of ships in the waters off Leyte. Moreover, constant air interdiction foredoomed any large concentration of shipping.

Along the northeastern coast of Cebu and in the port of Cebu itself, however, there were many landing craft and other vessels which had been used to run the enemy blockade. It was estimated that about 40 landing barges plus numerous small boats and bancas, could be assembled for the evacuation.22 Accordingly,

[532]

PLATE NO. 129

Final Defense-Leyte, 21 December 1944-late March 1945

[533]

the Army dispatched a staff group, designated the Rear Area Command Post, to Cebu on 4 January to procure and control all available shipping, as well as to arrange for the transport of rations and ammunition to Leyte on the eastbound trip.23 The staff group was also charged with liaison between Army headquarters and Army troops stationed on other islands of the central and southern Philippines with regard to expediting operational preparations.24

The planning had progressed sufficiently by 5 January to initiate the evacuation on a small scale.25 About 200 men of the 102d Division headquarters, including Lt. Gen. Shimpei Fukue, division commander, set out from Baliti in 25 bancas. Due to the unseaworthiness of some of the craft and the enemy's sea blockade, however, only 35 men, including the division commander, reached Tabog on, Cebu.26

On 8 January, Thirty-fifth Army completed an over-all plan covering the proposed evacuation.27 The following provisions were included:28

1. The 1st Division, 5th Infantry, and 380th lndependent Infantry Battalion will move to northern Cebu.

2. The 26th Division will transfer to the Bacolod sector of Negros.

3. The 41st and 77th Infantry Regiments will, if possible, return to the command of the 30th Division on Mindanao. Otherwise, these regiments will proceed either to Tagbilaran on Bohol, or to Dumaguete on Negros.

4. Elements of the 102d Division on Leyte will return to their original stations in the Visayan area.

5. The 16th Division, 68th Brigade and remnants of other units will remain on Leyte to cover the evacuation.

6. Army headquarters, with parachute regiments, will transfer to Cebu and subsequently to Mindanao, the withdrawal commencing after the majority of forces have withdrawn.

Implementing orders were to be issued according to the availability of transportation and

[534]

the progress of the assembly of units in the Canguipot area. The 1st Division was ordered on 8 January to board evacuation craft near Abijao, the first group embarking on the 12th. Enemy attacks in this area made it necessary for the next three echelons to load at Tibur on the 15th, 17th, and 20th.29

By this time the enemy had become aware of the attempted evacuation and subjected both embarkation and debarkation points to terrific air and surface attacks, destroying most of the Japanese craft. Concurrently, enemy ground forces launched an intensive clean-up campaign throughout northwestern Leyte to wipe out the remaining pockets of resistance. The evacuation therefore had to be temporarily suspended.30

Meanwhile, all Army units had finally received the order to withdraw into the mountainous area west of Highway 2. The remnants of the Imabori Detachment, Mitsui Shipping Unit, and 77th Infantry Regiment, numbering about 1,500, required almost a month to reach the Canguipot area, arriving early in February.31 The 26th Division, after initiating the retreat from the Lubi trail area during mid January, encountered the enemy at Valencia on 28 January. Following a brief skirmish, the Japanese withdrew and subsequently sifted through the enemy lines in small groups, approximately 800 survivors reaching the Canguipot area late in February.32 The remnants of the 16th Division were still en route.

By late February, it had become apparent to Army headquarters that no further large-scale evacuations could be undertaken. Although the tattered forces on Leyte still controlled some of the commanding terrain along the shoreline and could, on occasion, infiltrate through enemy patrols to gain the coast, enemy air and torpedo boat attacks had all but wiped out Japanese surface transportation.

Nevertheless, in the middle of March, Lt. Gen. Suzuki decided to attempt the transfer of his headquarters in accordance with the plan of 8 January.33 After dispatching an advance party on 17 March, Lt. Gen. Suzuki relinquished direct command over the Leyte remnants to Lt. Gen. Makino, commander of the 16th Division. The 300-odd survivors of this division were just arriving in the Canguipot area. The Army Commander, on 23 March, set out for Cebu by small boat.34

The weak and exhausted remnants still left on Leyte had long since ceased offensive operations. Lt. Gen. Makino, nevertheless, held his troops in the Canguipot area until late April when the shortage of food and relentless enemy clean-up campaigns forced them to retreat northeast to the vicinity of Bagacay. Shortly thereafter the order to disperse was issued, and centralized command ended.35

[535]

Meanwhile, the enemy had already launched his campaign to clean out Japanese garrisons throughout the central and southern Philippines.36 Palawan, the first to feel the impact of this mop-up,37 had by late February lost much of its importance to the Japanese. In possession of the enemy, however, the island would provide an excellent base from which air domination of the South China Sea could be made more complete.

Extending almost 300 miles in a northeasterly direction from the northern tip of Borneo, Palawan had been used by the Japanese as a stepping-stone in sea and air traffic between the Philippines and Borneo.38 Two airstrips, a seaplane base, and a good harbor at Puerto Princesa formed the hub of this important communications link. Moreover, the long coastline provided a sheltered passage and innumerable safe anchorages for the small supply and troop-carrying craft plying between Luzon and Borneo.

Enemy land-based aircraft operating from Leyte airfields had largely deprived Palawan of its value to Japanese communications. However, the heterogeneous collection of small Japanese units stationed in the area remained there since they could not be transferred elsewhere because of the lack of shipping.39

On 21 February, Maj. Gen. Takeshi Kono, 77th Infantry Brigade commander, dispatched a message to the Palawan garrison from his headquarters at Bacolod, ordering the various

[536]

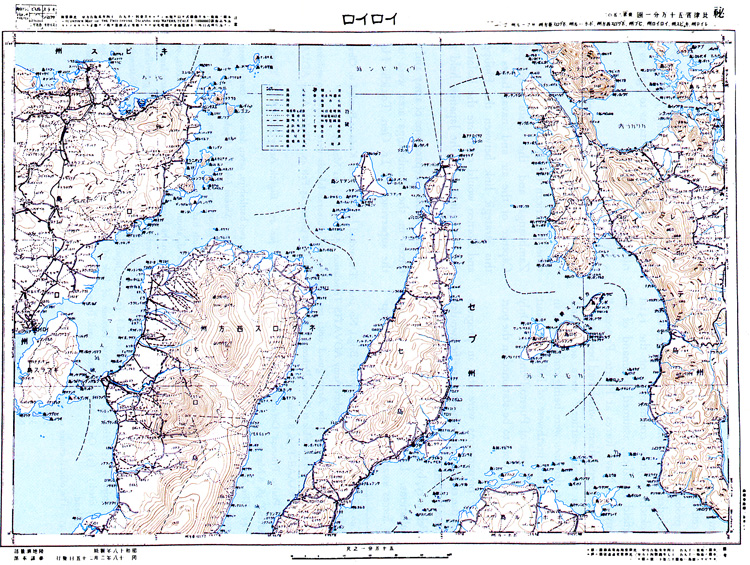

PLATE NO. 130

Map of Central Philippines Printed in 1943 by Land Survey Department,

Imperial General Headquarters

[537]

Army and Navy units stationed there to be placed under unified command and to prepare for probable enemy invasion.40

Under the provisions of this order, Capt. Chokichi Kojima, commander of the 131st Airfield Battalion, assumed command of all Army and Navy forces at Puerto Princesa.41 Defensive preparations, which had been started almost a month earlier,42 were accelerated. The main defenses were being constructed in the mountains northwest of Irahuan, about six miles northwest of Puerto Princesa. Only small outposts were to be stationed in the port city.

These preparations were still in progress when the enemy commenced a terrific two-day air bombardment followed, on the morning of 28 February, by an intensive shelling of coastal installations. Later the same morning, American forces swarmed across the beaches unopposed,43 the outposts having already withdrawn to the main positions. Shortly thereafter, on 2 March, the main defenses also began to crumble, and the surviving Japanese troops dispersed into the mountains to fight as guerrillas.44

On the heels of the invasion of Palawan, other American forces swung south to invade Zamboanga and the Sulu Archipelago. Capture of the air and naval bases along this strategic link between the Philippines and Borneo would complete the isolation of the Philippines from the Japanese-held areas to the south.

Joint defense preparations of army and navy forces in the Zamboanga area were under the supervision of Lt. Gen. Tokichi Hojo,45

[538]

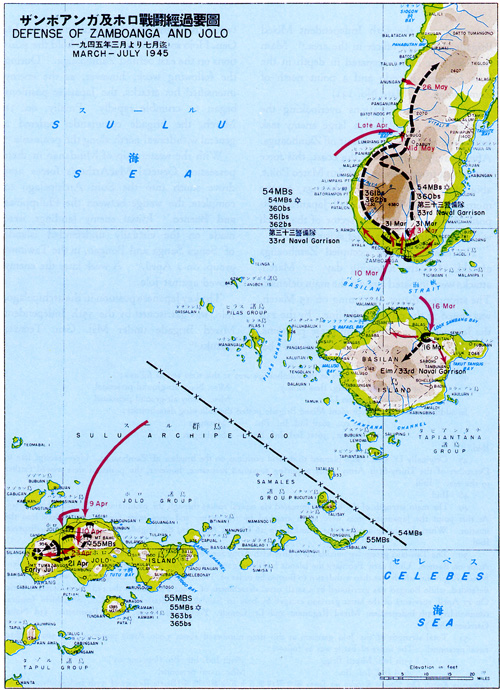

commander of the 54th Independent Mixed Brigade and senior officer in the area.46 Main defenses were being prepared in depth in the hills between Recodo and a point north of Zamboanga.47 (Plate No. 131)

Before these fortifications overlooking the beaches were completed, a large enemy task force appeared in Basilan Strait off Zamboanga. After heavily bombarding the coast, this force put assault troops ashore near San Mateo Point, about four miles west of Zamboanga, on the morning of 10 March. Small Japanese out posts stationed along that sector of the beach withdrew inland after a brief skirmish.48

The enemy quickly occupied Zamboanga airfield. On the following day, 11 March, attacks were initiated against the main defenses. The strongest thrust, beginning on 15 March, was aimed at the center of the line. By the 23d the Japanese were driven from these positions.

With communications now severed between the right and left flank positions, Lt. Gen. Hojo sought desperately to hold the positions on the east behind Zamboanga. During the following week, however, as the enemy intensified his attacks, the Japanese positions began to crumble rapidly. Finally, on 31 March, the brigade commander ordered a general withdrawal north along the peninsula.49

With the western tip of Mindanao in their possession, General MacArthur's forces now drove south into the Sulu Archipelago to complete the wedge between the Philippines and Borneo. Initial enemy landings were made on the virtually undefended islands of Sanga Sanga and Bongao, in the Tawitawi group, on 2 April.50 A week later the enemy moved against Jolo.

The key Japanese position in the archipelago, Jolo, was garrisoned by the 55th Independent Mixed Brigade under Maj. Gen. Tetsuzo Suzuki.51

[539]

PLATE NO. 131

Defense of Zamboagna and Jolo, March-July 1945

[540]

Under the general policy of fighting delaying actions throughout the central and southern Philippines, Maj. Gen. Suzuki had abandoned earlier plans for defending the beaches and organized inland positions in depth back of the capital city of Jolo, on the north side of the island. Forward positions were prepared on scattered hills in the open terrain to the east of the city, covering the airfield, while the main defenses were farther to the rear in the more mountainous areas to the southeast and southwest.52 The field fortifications were fairly well completed by early April, with sufficient rations stored near each position to last about one month.

During the night of 8-9 April, American naval craft stood into the coast, and on the following morning, after a heavy naval and air bombardment, an estimated 3,500 troops, supported by tanks, landed near Tagibi, eight miles east of Jolo. Before nightfall a smaller enemy detachment had effected a second landing nearer the city.

The Japanese forces were extremely hard pressed from the first because of the open terrain in which the forward positions were located. These were quickly overrun, and the enemy continued his frontal assaults in conjunction with guerrilla attacks from the rear. The day after the landing, the main enemy force began attacking the 365th Independent Infantry Battalion's mainline positions southeast of Jolo. Within ten days the battalion was driven from these positions, and on 21 April, Maj. Gen. Suzuki ordered it to withdraw to Mt. Tumazangos, about five miles southwest of Jolo.

Before the battalion could complete its movement, the enemy launched an attack against the Japanese positions in the Mt. Tumazangos sector. Enemy pressure eased after the early part of May, however, and the Japanese forces found time to reorganize their ranks.53 Thereafter they were subjected only to sporadic guerrilla attacks.

Even before the conclusion of the enemy campaign to gain control of the strategic island links between the Philippines and Borneo, General MacArthur had launched another series of amphibious operations in the central Philippines. The objective of these operations was to wipe out remaining Japanese concentrations in the Visayan group of islands.

The largest concentration of army forces in the Visayan area was on northwestern Negros, formerly Fourth Air Army's most important base south of Luzon. Eight airstrips dotted the northwest part of the island, mostly centered around the town of Bacolod.54 As of mid-March, Japanese strength in the area totalled almost 12,000, the major part of which was

[541]

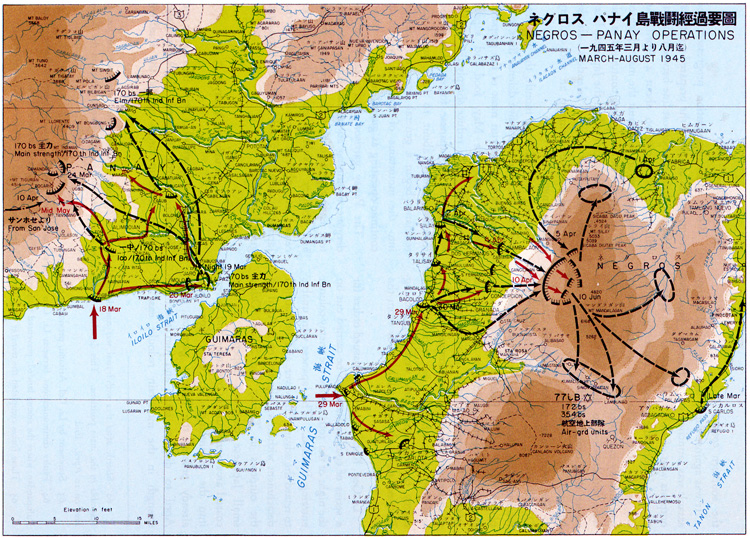

made up of airfield troops and miscellaneous ground personnel of the 2d Air Division.55 Regular ground combat troops were limited to two infantry Battalions of the 77th Infantry Brigade, 102d Division, although provisional combat units were rapidly being organized from the air ground and service units.56 Lt. Gen. Takeshi Kono, brigade commander; directly controlled these troops in addition to exercising general command of Army ground forces on Panay and adjacent islands.57

Lt. Gen. Kono had recognized some time earlier that a prolonged defense of the airfields themselves was not feasible because of the flat terrain. To comply with the terms of the Thirty-fifth Army order requiring sustained resistance, he had decided to deploy the main strength of his troops in the nearby mountains, from which raiding squads could be dispatched.58 (Plate No. 132) Small detachments were to be stationed near probable landing points, in towns, and near airfields59 to delay the enemy's approach to the main defenses.

On the neighboring island of Panay, the Japanese garrison also prepared its main defenses in the mountains.60 Simultaneously with an enemy landing, the main strength was to withdraw from Iloilo to the Bocari area, about 20 miles northwest of Iloilo.61 Only small outposts were stationed along

[542]

the southern coast.

It was against Panay that the initial enemy assault was launched on 18 March. Japanese outposts west of Iloilo fell back as the enemy advanced along the coast to enter the capital city on the 10th. The small Japanese forces had already evacuated the city as planned and were withdrawing to the mountain redoubt, where they completed their assembly by 24 March.62

The enemy now turned to attack Negros. On 28 March, Lt. Gen. Kono's headquarters received radio reports from Japanese transport planes flying out of Bacolod that an enemy convoy had been sighted near Inampulugan Island in Guimaras Strait.63 No further word of this enemy force was forthcoming until the following day, when it was reported that enemy tank-infantry teams were approaching Bacolod along the coastal highway from the South.64

Lt. Gen. Kono immediately issued orders for a series of counterattacks to be carried out on the night of the 30th against the enemy column entering Bacolod. The Japanese were unable to retard the advance, however, and the Bacolod detachment withdrew, followed on 2 April by the outposts in Talisay and Silay. Other small Japanese garrisons dispersed in the coastal area were quickly overcome and driven into the mountains. Lt. Gen. Kono had already ordered the Fabrica garrison on 1 April to displace south and join the main strength in the mountain redoubt east of Bacolod.65

While this concentration progressed, the enemy began attacking the prepared positions. After crushing the outpost line between Guimb alaon and Concepcion about 4 April, the enemy pressed on to assault the main defenses on 10 April. Bitter fighting continued in this area until late April, when the Japanese lines slowly crumbled under relentless attacks supported by overwhelming air and artillery bombardment.

During the following month, the Japanese were driven from successive defense lines until the enemy had overrun most of the prepared positions. By late May, food and supply shortages began to reduce sharply the combat efficiency of the Japanese forces. Organized resistance ended about 10 June, when the remnants began a general retirement deeper into the mountains of northern Negros to continue operating as guerrillas.66

The Panay garrison had meanwhile undergone, beginning about mid-April, intermittent enemy ground assaults supported by air and artillery bombardment. These attacks ceased altogether in late May. Thereafter the Japanese were harassed only by occasional guerrilla raids.

Concurrently with his drive into Panay and Western Negros, General MacArthur also moved clean-up forces against the southern

[543]

PLATE NO. 132

Negros-Panay Operations, March-August 1945

[544]

islands of the Visayan group. The most important and strongly defended of these was the island of Cebu.

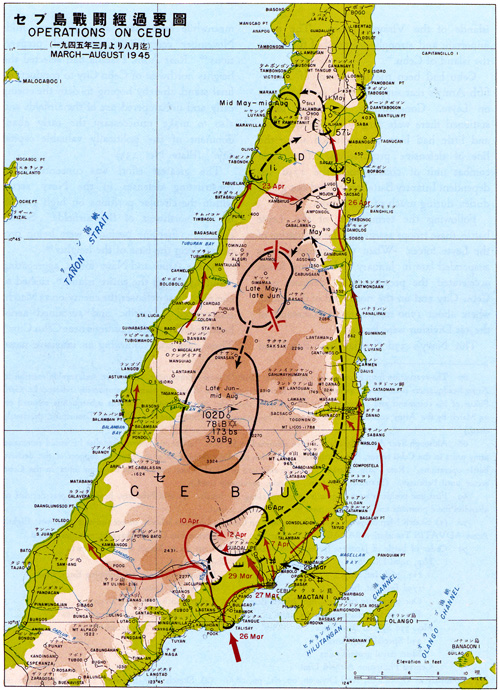

Cebu had been the focal point of Thirty-fifth Army's rear support of the decisive battle on Leyte. Consequently, the Army forces stationed there were largely service elements, and little had been accomplished along the line of defensive preparations. The single combat unit of consequence, the 173d Independent Infantry Battalion, carried out guard duties during much of this period.

Following the termination of the Leyte battle, these troops assisted in the evacuation of the Leyte forces. When the evacuation was suspended late in January,67 the Army forces accelerated the preparation of defenses near Cebu City and on the north end of the island, where about 1700 troops under command of the 1st Division were located.

The Navy's 33d Special Base Force had meanwhile been hard at work since mid-November completing operational preparations.68 Rear Adm. Harada had selected the heights northwest of Cebu City to conduct the final stand, thereby hoping to deny the enemy early and unhampered use of the airfields and also to make unnecessary the early abandonment of the politically valuable capital city. (Plate No. 133)

The greatest effort was concentrated in constructing defenses in the Navy sector within the circular positions on high ground to the northwest of the airfields. Simultaneously, first-line positions were being pre pared along the base of the heights.69

As the Army and Navy forces, aggregating about 14,500 on the entire island,70 rushed to complete these defenses, the enemy, on 23 March, commenced a terrific and sustained aerial bombardment of the positions near Cebu City.71 Three days later, following an intensive naval

[545]

PLATE NO. 133

Operations on Cebu, March-August 1945

[546]

shelling, the enemy put ashore at Talisay an invasion force estimated at about one division.72 The weak Japanese outposts were quickly overcome as the enemy moved out of the beachhead toward Cebu City.

On the same day that the landing took place, Lt. Gen. Suzuki, Thirty-fifth Army Commander, arrived in Cebu City en route from Leyte to Mindanao. Before departing for northern Cebu to continue his journey, Lt. Gen. Suzuki ordered Lt. Gen. Fukue, 102d Division commander, who had been placed in over-all command of the forces in the Cebu City area on 24 March,73 and Rear Adm. Harada to defend the present positions in the heights sector as long as possible. Other provisions of this order included the following:74

1. When the continued defense of these positions becomes impossible, withdraw to northern Cebu and continue resistance.

2. After joining with the 1st Division, the head quarters of the 102d Division and its original sub-ordinate units will move to Negros and command the units stationed on that island. Upon the departure of the 102d Division headquarters, the lit Division commander will assume command of all units on Cebu.

Shortly after receiving this Army order, Lt. Gen. Fukue issued the following plan of operations for the defense of the positions northwest of Cebu City:75

1. The greatest effort will be made to secure the highest mountain position and the naval positions.

2. Withdrawal from these positions is tentatively scheduled for about 20 April. Rations for one month must be preserved for consumption following the withdrawal.

3. Movement from the present positions will be to the northeast via Liloan to northern Cebu.

4. Forces making the withdrawal will reassemble in the sector north of the Lugo-Tabuelan road.

The enemy had meanwhile entered Cebu City on 27 March. After overrunning the airfields, tank-infantry teams forged ahead to the newly-prepared first-line positions, which the Japanese defended briefly before retreating up the heights to the main positions.

Frontal attacks against these well-organized positions began on 29 March. Repeated assaults during the first week of April failed to score more than small local penetrations on the southeast flank defended by the naval forces. On the southwest flank, however, the Army positions were breached at several points. Unremitting air and naval bombardment supporting the enemy ground attacks also inflicted heavy damage on the Japanese positions and rear installations and seriously lowered the morale of the troops.76

Having registered only limited gains by his frontal attacks on the left flank, the enemy, on 7 April, began to encircle the naval positions on the northeast. This advance threatened to sever the route over which the Japanese planned to withdraw northward. The

[547]

naval forces therefore launched a prompt counterattack, which temporarily halted the enemy drive.

An enemy force now moved around the southwest flank and gained the rear of the Japanese positions. Attacks were launched against the highest point of the defenses on 10 April. Although this particular sector had been recognized by the Japanese as the most vulnerable point because of unfavorable defensive terrain, shortage of combat troops had made it impossible to adequately defend the area. The enemy consequently broke through successive defense lines within a few days. By 12 April the defenses on the northwest flank of the circular position were almost completely overrun.

In view of the rapidly deteriorating situation, Lt. Gen. Fukue decided on 12 April that the withdrawal to northern Cebu should be initiated. Orders were issued the following day,77 and the general retirement actually began on the night of the 16th. During the following two weeks, the Japanese remnants, harassed by enemy ground pursuit, air attack, and naval shelling, retreated to the north. By avoiding a pitched battle, the survivors reached the area south of the Sacsac-Tabuelan road by 1 May.78

Swift enemy columns had meanwhile raced ahead to occupy this road, preventing the Japanese retreating northward from effecting a juncture with the weak forces north of the road. The plan to transfer the 102d Division elements to Negros was therefore dropped.

When the enemy began attacking positions north of the road on 23 April, the 1st Division, which had been mainly preoccupied since its arrival from Leyte with fighting guerrillas, was ill prepared to meet the enemy drive. The defenses near the coast first gave way, followed two weeks later by the crumbling of the center of the line. By 11 May further defense of the area had become impossible. Lt. Gen. Tadasu Kataoka therefore ordered all units to disperse into the mountains west of Ilihan.79

Shortly thereafter the enemy extended his clean-up operations to the mountain area south of the road, where the remnants of the 102d Division had taken temporary refuge. By late June the survivors in this area were forced to disperse deeper into the mountains to the south.

Concurrently with the fighting on Cebu other enemy forces had launched two new invasions to complete the conquest of the neighboring island. The first landing was made on 11 April at Tagbilaran, Bohol, and was unopposed by the small Japanese garrison which had already withdrawn into the mountains.

The second landing was made shortly thereafter on 26 April near Dumaguete, eastern Negros, which had been an advance base for the midget submarines operating out of Cebu and a liaison point between the Visayas and Mindanao. This Japanese garrison was also too weak to permit more than a brief defense of the forward positions before withdrawing into the interior. In mid June the survivors broke up into small groups to operate as guerrillas.80 Organized resistance had now ceased throughout the Visayas.

[548]

Defense Preparations on Mindanao

With the enemy moves against Cebu and Bohol in late March and early April, the main portion of Mindanao to the east of the Zamboanga Peninsula remained the only important sector of the Philippines which had not yet felt the impact of General MacArthur's liberating forces. Here, Lt. Gen. Gyosaku Morozumi, in over-all command of army forces east of Lake Lanao, sped final preparations to meet invasion.

Army and navy forces deployed in this sector totaled about 58,000 far more than had been available for the defense of any other island. In addition to these regular forces about 17,000 Japanese civilians, of whom about 5,000 were employed as laborers, still resided in the large Japanese colony at Davao.81

In spite of this numerical strength, an inadequate road net dividing the area into two distinct and widely separated tactical sectors militated against a rapid transfer of troops to meet an enemy invasion.82 In central Mindanao, extending from Cotabato, on the eastern shore of Moro Gulf, to Surigao on the north, Lt. Gen. Morozumi exercised direct command over the ground forces. The remnants of the Army air forces in this area were still under the command of Lt. Gen. Seiichi Terada, commander of the 2d Air Division, who had only recently transferred from Bacolod.83 (Plate No. 134)

Defense of the remainder of the area was charged to Lt. Gen. Jiro Harada, commander of the 100th Division.84 In addition to the

[549]

PLATE NO. 134

Dispositions on Mindanao, 16 April 1945

[550]

troops now under his command, about 7,700 Navy ground personnel were stationed in the Davao and Digos areas under Rear Adm. Naoji Doi, 32d Special Base Force commander, who had organized these troops into four provisional battalions. Also in this area were the 13th Air Sector Unit, under the 2d Air Division, and the remnants of the Southern Philippine Airfield Unit, still under Southwest Area Fleet control. All of these Navy and Air force units were to come under operational control of the senior Army commander in case of an enemy invasion.

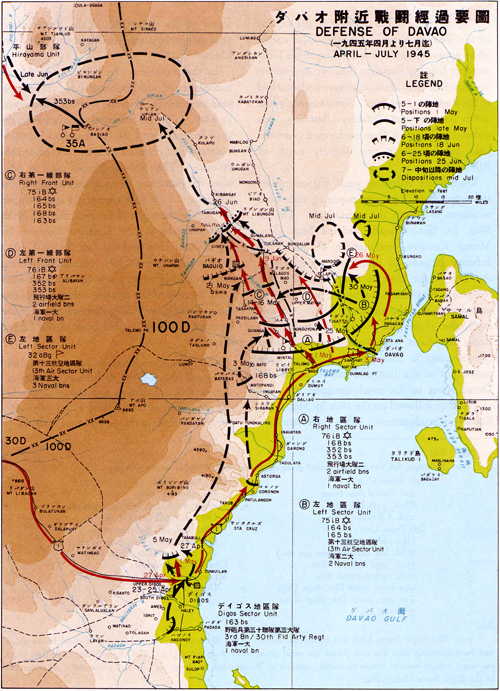

The launching of the enemy clean-up cam paign in the southern Visayas during late March and severe air raids on key points in Mindanao early the following month stimulated belief that an invasion of Mindanao was imminent. Lt. Gen. Morozumi estimated that the main enemy thrust would be delivered against either Cagayan or Davao, probably the former, with a possible secondary landing on a smaller scale in the Cotabato area.85 No plans were entertained, however, for strengthening the Cagayan area at the expense of the defenses near Davao.

Operational preparations of the tooth Division, the main strength of which had been concentrated near Davao since September 1944, were well advanced by mid-April.86 Lt. Gen. Jiro Harada still believed that the enemy would launch an amphibious invasion of the Davao area, the main assault falling just east of Daliao.87 Positions were therefore constructed facing southeast on both sides of the Davao River. Disposition of the division at this time was as follows:88

| Davao Area |

| .....Right Sector Unit (west of Davao River): |

| ..........Hq., 76th Inf. Brig. |

| ..........168th (less one co.), 352d, and 353d Ind. Inf. Bns. |

| ..........Two engr. cos. |

| .....Left Sector Unit (east of Davao River): |

| ..........Hq., 75th Inf. Brig. |

| ..........164th and 165th Ind. Inf. Bn. |

| ..........One arty. btry. |

| ..........One engr. co. |

| .....Arty. Unit: |

| ..........100th Division Arty. Unit (less one btry.) |

| .....Reserve: |

| ..........One co., 163d Ind. Inf. Bn. |

| ..........167th Ind. Inf. Bn. (less two cos.) |

| Digos Sector Unit: 89 |

| ..........163d Ind. Inf. Bn. (less one co.) |

| ..........3d Bn. (less two Btrys.), 30th Fld. Arty. Regt., 30th Div. |

| Sarangani Sector Unit: 90 |

[551]

| ..........One co., 167th Ind. Inf. Bn. |

| East Coast Unit (en route to Davao): 91 |

| ..........One co., 167th Ind. Inf. Bn. |

| ..........One co., 168th Ind. Inf. Bn. |

Plans had been prepared to incorporate the naval forces into the existing tactical grouping of the tooth Division. The 11st and 2d Naval Battalions were to be attached to the Left Sector Unit, the 3d Battalion to the Right Sector Unit, and the 4th Battalion to the Digos Sector Unit.92

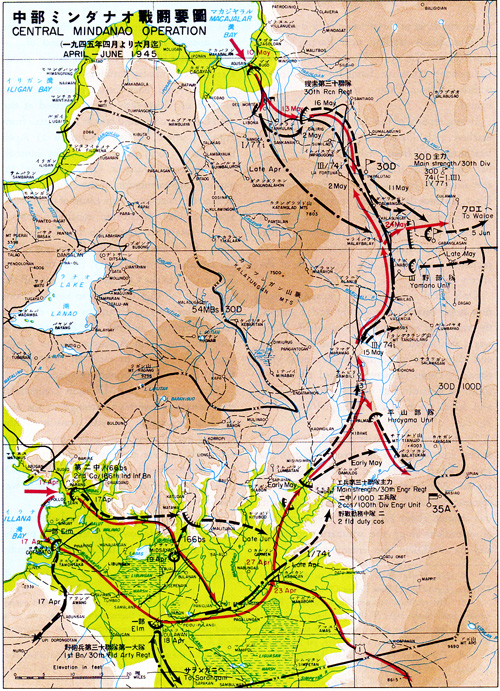

In central Mindanao, where there were fewer troops to cover a far greater area, operational preparations of the 30th Division had been virtually stalemated because of other urgent requirements. An acute shortage of foodstuffs prevailing in the upper highlands along Highway 3 since August 1944 made it necessary to employ troop units to gather provisions, particularly rice in Cotabato Province, and to transport them over the inadequate road net to the Malaybalay sector.

With the realization early in April that an enemy attack was imminent and that the danger to Cagayan was increasing, Lt. Gen. Morozumi called a halt to these foraging activities and speeded up the division regrouping which had been started more than three months previously. By mid-April, three widely scattered elements were moving toward the northern part of central Mindanao.

The 3d Battalion, 41st Infantry, had recently arrived in the Ampayon area en route to Balingasag from Surigao.93 The main strength of the 11st Battalion, 74th Infantry, had just been ordered to suspend the collection of supplies in the Dulawan area and was near Kabacan en route north to join the main strength of the regiment. Farther south, the 11st Battalion, 30th Field Artillery Regiment, was in Dulawan on its way north from Sarangani Bay.94 The tactical grouping of the 30th Division was now as follows:

| Surigao Sector Unit: |

| .....3d Bn., 41st Inf. |

| North Sector Unit: |

| .....30th Rcn. Regt. |

| .....1st Bn., 77th Inf. |

| Central Sector Unit: |

| .....74th Infantry Regt. |

| Under Division Control: |

| .....30th Fld. Arty. Regt. (less 3d Bn.) |

| .....30th Engr. Regt. (less 2d and 3d Cos.) |

| .....30th Trans. Regt., reinf. |

| .....Misc. division troops |

| South Sector Unit:95 |

| .....One co., 1st Bn., 74th Inf. |

| .....Two field duty cos. (temporary) |

| .....Misc. units |

| West Sector Unit: |

| .....166th Ind. Inf. Bn. |

The northward shift of 30th Division troop strength to meet an expected invasion of the Cagayan area was in full swing when the enemy

[552]

struck suddenly at the division back door with an amphibious landing near Parang on 17 April. (Plate No. 135) Outposts of the 166th Independent Infantry Battalion had already withdrawn from Parang to positions farther inland.

Before reports of this latest American move reached 30th Division headquarters, a firm beachhead had been established in the Cotab ato area. As the enemy forces advanced east along the highway and up the Mindanao River, Japanese detachments destroyed the highway bridges and withdrew. The main strength of the 166th Independent Infantry Battalion also withdrew from the Midsayap area to prepared positions on the north flank of the enemy column.96

Only small miscellaneous Japanese forces now stood between the enemy and Kabacan, the vital road net junction from which Highway 1 continued southeast to the Davao area and Highway 3 ran north through central Mindanao. These elements engaged the enemy south of Kabacan but were quickly overcome and driven north of the Pulangi River on 23 April.97

By this time 30th Division headquarters had swung into action in an attempt to stem the enemy advance before it moved north into central Mindanao. Col. Koretake Ouchi, commander of the 30th Engineer Regiment, was ordered about 22 April to take command of operations along the southern approaches and to annihilate the enemy south of the east-west line running through Omonay. For this mission he was given command of the South Sector Unit and the equivalent of about a reinforced infantry battalion.98

On 23 April, Maj. Gen. Tomochika, Chief of Staff of Thirty-fifth Army, arrived at the 3oth Division command post at Impalutao from Agusan, where he had arrived on 21 April from Cebu. Maj. Gen. Tomochika immediately conferred with Lt. Gen. Morozumi regarding implementation of the Army policy of protracted resistance. As a result of this discussion, Lt. Gen. Morozumi concluded that it was necessary to strengthen the Malaybalay area. He therefore ordered the transfer of the 1st Battalion, 77th Infantry, from the North Sector Unit to the Central Sector Unit and the movement of this battalion to new positions near Malaybalay. About the same date Lt. Gen. Morozumi ordered the Surigao Sector Unit to move from Ampayon to the Waloe area, where it was to assist in carrying out the division's self-sufficiency program.

Although the 30th Division commander thus adopted measures to strengthen the area of final resistance, he still considered the landing near Parang a secondary invasion and estimated that the main enemy landing would soon be launched in the Macajalar Bay area.99 The preponderance of division strength was therefore retained in the north.

With regard to the protracted defense of Mindanao, the following plan, based on the policy under study by the Army Commander

[553]

PLATE NO. 135

Central Mindanao Operation, April-June 1945

[554]

since the Leyte campaign, was evolved on 28 April:100

I. General Policy

The Army will repel the invading enemy. When this is no longer possible, the forces will remain in the southern Philippines, strive to reduce the enemy's combat strength and prepare to support future Japanese counterattacks, thus contributing to the over-all operations.

II. Outline of Operations

1. A portion of the 30th Division will cooperate with the 100th Division in operating against the enemy advancing from Cotabato Province to the Davao area. The main body of the 30th Division will endeavor to reduce the combat strength of the enemy penetrating into central Mindanao and will establish a primary self-supporting region in the area east of Malaybalay. Preparations will be made later to establish a second self-supporting area near Waloe. The forces preparing defenses in the north near Del Monte will be reduced as much as possible.

2. The 100th Division, concurrently commanding the Army air ground and service troops and Naval forces, will attempt to crush the enemy invading the Davao plain from its present positions. It will establish strong self-supporting regions in the areas north of Davao, north and west of Tamugan, and on the east slope of Mt. Apo. The mouth of the Tagum River and its vicinity will be secured by portion of its strength.

3. The Yamano Unit (Army air ground service troops in central Mindanao) will establish a self-supporting region in the area east of Mailag.101 It will then expand the region to the south and will cooperate with operations of the 30th Division.

4. The Hirayama Unit (57th Field Road Construction Unit and attached miscellaneous elements) will defend the rear of the Tooth Division and the western front of the Army self-supporting region against American forces expected to penetrate into the Davao area along the Palma-Tamugan road.

After implementing orders were issued by Lt. Gen. Morozumi, Maj. Gen. Tomochika moved to Basiao to establish the Thirty-fifth Army Command Post and await the Army commander, who had not yet arrived from Cebu.102

Meanwhile the enemy paused only briefly at Kabacan before launching a drive southeast along Highway 1 toward Davao on 23 April. Four days later another column resumed the advance north along Highway 3 in what appeared to be an offensive in considerable strength. Lt. Gen. Morozumi promptly decided upon a further shifting of troops in the north. He ordered the 3d Battalion, 74th Infantry, to withdraw from Dalirig to Malaybalay and the 30th Reconnaissance Regiment to pull back from Del Monte airfield to occupy the positions near Dalirig vacated by the 3d Battalion.

The forces under Col. Ouchi were by this time proving inadequate to cope with the enemy column advancing along the highway. Successive road blocks and delaying detachments were overrun as the enemy pushed rapidly north. To reinforce this sector with additional infantry strength, the division commander, on 2 May, ordered the 3d Battalion, 74th Infantry, which had just arrived at Impalutao, to continue marching south to Maramag and block the enemy advance. Shortly after arriving, the battalion, on 15 May, launched a counterattack against the head of the enemy column but the Japanese were quickly pushed aside. The road

[555]

to Malaybalay from the south now lay open.

The 3oth Division had, in the meantime, come under attack from the north. An enemy force, estimated at about one regiment, landed at Agusan on 10 May and pushed rapidly inland, opposed only by small outposts. The following day, Lt. Gen. Morozumi ordered the division headquarters, which had been preparing to move, to transfer from Impalutao to the strongpoint east of Malaybalay.

The main defenses of the 30th Reconnaissance Regiment near Dalirig were brought under attack on 13 May. Three days later, after the enemy had overrun the last of these positions, Lt. Gen. Morozumi ordered the remnants to withdraw to the east of Malaybalay.103 Shortly thereafter, on 23 May, the two enemy columns from the north and south effected a juncture at Impalutao.

On the following day the first-line defenses east of Malaybalay were subjected to a terrific artillery bombardment. The enemy followed this with a strong ground assault which the Japanese were able to check only temporarily. By 5 June, the division was driven back to positions near the Pulangi River. On that date Lt. Gen. Morozumi ordered a withdrawal to the Waloe area.104 The 30th Division was thereafter unable to mount more than small-scale raiding forays.105

Meanwhile the enemy column driving southeast from Kabacan had pushed swiftly along Highway 1 before the Japanese could organize effective delaying action and entered Digos on 27 April. Outposts of the Digos Sector Unit delayed the enemy force briefly before retreating to the main positions in the mountains to the northwest.106 (Plate No. 136) A smaller force, dispatched from the Right Sector Unit in Davao to positions near Astorga, was overcome following a short engagement. The enemy column moved on into Davao on 3 May.

The enemy had meanwhile begun attacking the first-line positions of the Right Sector Unit on both banks of the Talomo River on 1 May.107 As more enemy elements closed into the Davao area, these frontal attacks spread to the east to include the Left Sector Unit on 3 May.

After moving division headquarters from Mintal to Lapuy, Lt. Gen. Harada took steps on

[556]

3 May to reinforce the defenses in the vicinity of the Talomo River, where the major enemy effort appeared to be aimed. The 167th Independent Infantry Battalion (less two companies) was removed from division reserve and attached to the Right Sector Unit. Simultaneously, the 168th Independent Infantry Battalion was ordered to pull back from its forward positions near Bayabas to a line slightly north of Mintal.108

During the following week, the enemy attacks grew steadily heavier, requiring additional measures to bolster the right flank. On 11 May, Lt. Gen. Harada ordered Maj. Gen. Muraji Kawazoe, commander of the 75th Infantry Brigade, to relinquish command of the Left Sector Unit to Rear Adm. Doi and redeploy a maximum number of his troops to new positions in the vicinity of Ula. Accordingly, the 164th and 165th Independent In fantry Battalions, each leaving approximately one company in the original positions, were pulled out of the line and moved across the Davao River to the newly-assigned area on 14-15 May, followed on the 16th by Maj. Gen. Kawazoe's headquarters. Two days later the forces on the right bank of the Davao River were reorganized into the Right and Left Front Units.109

In the meantime, the fighting near Mintal had continued with unabated fury. The Japanese were driven from the forward positions on 11 May. On the following day, however, the 353d Independent Infantry Battalion launched a determined counterattack and recaptured the defenses. The battle continued until 24 May when the American forces again reoccupied the positions. This time they could not be driven off.110 On the night of the 25th the Left Front Unit withdrew to new positions between the Right Front Unit and the Left Sector Unit.

Four days later Lt. Gen. Harada, foreseeing eventual independent action by the Left Sector Unit because of the terrain, issued the following order to cover subsequent operations of the Japanese forces on the left bank of the Davao River:111

Rear Adm. Doi will remain in command of all Army and Navy forces on the left bank of the Davao River and will destroy the enemy in that area. Should the situation require a withdrawal, the forces remaining on the left side of the river will move to the upper

[557]

PLATE NO. 136

Defense of Davao, April-July 1945

[558]

reaches of the Davao River, where they will carry out self-sustaining operations.112

Meanwhile, the enemy had quickly followed up the withdrawal of the Left Front Unit to launch attacks against the Japanese positions near Ula on 27 May. By 1 June these positions were overrun. The enemy pressed for ward to capture Wangan on the 16th and Culanan on the 19th. All of the prepared defenses were now in the hands of the American forces.

While the 100th Division remnants assembled along the line of the Tamogan River, Lt. Gen. Harada decided on 26 June to withdraw still farther in order to take advantage of more favorable terrain. Accordingly, he ordered the 76th Infantry Brigade to take up positions about four to six miles north of the Tamogan River and the 75th Infantry Brigade to occupy positions farther north near the Bannos River.113

As the withdrawal to the new positions got under way, a fresh enemy threat to the division rear from central Mindanao began to take shape. The Hirayama Unit, defending the area southeast of Palma,114 was forced back by late June to the juncture of the Pulangi and Kulaman Rivers. Lt. Gen. Harada, pursuant to an Army order, promptly ordered the 353d Independent Infantry Battalion to move to the south bank of the Kulaman River and defend that area.115

About 11 July it was reported that the American forces had been replaced by large guerrilla forces. Although the enemy pressure eased thereafter, Lt. Gen. Harada issued orders to disperse and forage for food in the vicinity of Upian, Basiao and the southern bank of of the Kulaman River.116 The remnants began to move to the designated areas on 15 July. Soon thereafter, enemy attacks ceased altogether.117

By late June, scarcely eight months after the invasion of Leyte, the once powerful Fourteenth Area Army in the Philippines was completely broken. The remnants, consisting of small isolated groups of survivors holed up in mountain areas, were more concerned with foraging for food than with offensive operations.

The strategic consequences of the loss of the Philippines were disastrous in the extreme. The sea lanes between the industrial area in the Homeland and the resources of the southern regions, which had been slowly withering under the relentless attacks of American submarines and long range aircraft,118 were now

[559]

completely severed by air and surface patrols operating from Philippine bases. Only the rapidly dwindling stockpiles in Japan and the limited amount of raw materials which could be obtained from China and Manchuria could hereafter feed the flagging war potential.119 Moreover, the Japanese armed forces helplessly isolated in the southern areas must henceforth depend entirely on the supplies already within those areas.

The Japanese High Command had thrown into the battle for the Philippines the maximum ground, sea and air strength which could be mustered in a desperate but futile attempt to halt the American advance grinding toward the heart of the Homeland. The decisive battle phase ended in failure when the enemy landed on Mindoro, 15 December 1944 .

Thereafter the only choice left to these Japanese isolated in the Philippine Islands was to inflict the greatest possible losses and delay on the American forces in the hope of postponing the invasion of the Homeland itself.

The defeat had cost the Japanese military machine dearly. The Navy surface forces suffered such a crippling blow in the battle for Leyte that the Combined Fleet was thereafter able to conduct only small-scale forays.

Losses in ground forces had totalled more than 500,000.120 Fourteen divisions, four independent mixed brigades, one regular brigade, about 50 provisional battalions organized from miscellaneous Army service units,121 and numerous naval and air elements had been destroyed in the bitter ground fighting since the enemy landing on the Leyte beaches on 20 October 1944 .

The tremendous losses in aircraft and trained flying personnel had influenced the adoption of special-attack, or tokko, methods by the Army and Navy air forces. This type of warfare had by now been accepted by the Japanese armed services as an essential feature of the plans for the defense of the Homeland.

[560]

Go to

Last updated 1 December 2006 |